At first, Wayne McGhie isn’t sure what all the fuss is about. As a late January blizzard hammers southern Ontario, McGhie, 57, is the center of attention inside his sister’s Toronto apartment. Among those who brave the whiteout to see him are longtime friend – singer Jay Douglas – and two men he’s never met before: Matt Sullivan, head of a Seattle record label, and Kevin Howes, a Canadian writer and DJ.

Over a Caribbean cook-up, prepared by McGhie’s sister Merline, memories of yesterday return in living color. But what happens next is one of those awe-inspiring moments that would make anyone (this writer included) forever rue having missed it. Sullivan pops a disc into the CD player and hits play.

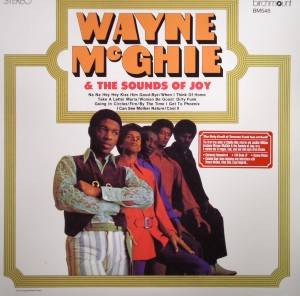

The song blasting from the speakers is “Na Na Hey Hey Kiss Him Goodbye.” Its hook has long been a staple at sports arenas. But this isn’t the original version from the studio musicians cobbled together to form the one-hit wonder, Steam. It’s Wayne McGhie. And the song is from his 1970 debut album, Wayne McGhie & The Sounds of Joy – a stellar work that blends soul, funk and reggae.

The song blasting from the speakers is “Na Na Hey Hey Kiss Him Goodbye.” Its hook has long been a staple at sports arenas. But this isn’t the original version from the studio musicians cobbled together to form the one-hit wonder, Steam. It’s Wayne McGhie. And the song is from his 1970 debut album, Wayne McGhie & The Sounds of Joy – a stellar work that blends soul, funk and reggae.

“Wayne’s face instantly lit up as soon as it came on. It was really emotional,” recalls Sullivan. Decades have passed since McGhie last heard the album. The music – his music – has brought such exhilarating highs and crushing lows. Unable to give voice to the memories that rush into his deeply-scarred mind, McGhie’s teary-eyed face says it all.

Away from the shadow of American R&B and British rock in the early 1960s, Jamaica sparked its own musical revolt with the horn-and-guitar driven riddims of ska. The first genre to set Jamaican dancehalls ablaze also gave the public its first glimpse of future legends like keyboardist Jackie Mittoo, singer Jimmy Cliff, and a pre-Rasta Bob Marley & The Wailers.

After impressing audiences and fellow musicians with his distinct sound, Wayne McGhie was recruited to take the music to an unlikely venue – Canada. With movie star looks and back-up gigs with Sly & The Family Stone, he seemed destined for fame. By the end of the ’70s, however, McGhie lost it all – his career, his daughter, and most dramatically of all, his own sanity.

As he plunged into a psychological hellhole, he disintegrated into a disheveled, unrecognizable shell of his former self – a journey that brought homelessness and a stay at a mental hospital. Only now has he awakened from the nightmare, thanks to some 20-something year-olds on a mission.

Wayne McGhie was born in Montego Bay, Jamaica in 1947. His father, Eustace, and his mother Julia, also had three daughters. Life was hard, but the family enjoyed a loving household. So it was only natural that after learning how to play a basic guitar scale from a local Calypsonian, Merline McGhie would give her brother lessons.

“I don’t think Wayne took it seriously,” she says. “He used to leave the guitar all over the place.” But not for long. He mastered the guitar scales and enrolled at the Montego Bay Boys’ School for formal music training. It was the late 1950s. And whether McGhie and a generation of budding musicians realized it or not, they were on the verge of impacting the world.

After nearly 300 years of British rule, Jamaica gained independence in August 1962. Yet a movement that was authentically Jamaican was well underway. For years, on the streets of Kingston and Trenchtown, foot-stompin’ American R&B filled the air. But when rock ‘n’ roll began to reign supreme in the early ’60s, the leading soundmen of the era – Clement “Coxsone” Dodd, Arthur “Duke” Reid, and Prince Buster – improvised new grooves.

Under their close supervision, musicians performed off beats that merged the folk genres of mento, calypso, and R&B to create new riddims. More than a decade later, a Jamaican-born DJ Kool Herc would follow a similar blueprint to create a new means of expression for frustrated ghetto youth in the bombed-out, boogie-down South Bronx.

The impact of ska hit immediately and spread like wildfire. “It was beautiful. Ska had a sweet, progressive beat,” remembers Jay Douglas. “We picked up [Miami radio station] WINZ and heard Smiley Lewis, Elvis and Rosco Gordon. That was our foundation.” Aspiring musicians like Douglas competed in local talent shows at clubs like Palladium. But getting there wasn’t easy.

First, the band had to meet the approval of legendary ska and reggae trumpet player Joseph “Jo-Jo” Bennett, who booked acts at the Palladium. Then they had to face audiences that made at The Apollo look like a genteel group of opera spectators. Often, Douglas competed against McGhie. “Oh God! Wayne just had that voice. He was a strong brother with determination in his eyes,” Douglas reflects.

Bennett also witnessed McGhie’s resolve when he booked him for a competition in 1962. “He was charismatic and didn’t look nervous,” he says. That night, McGhie was the uncontested winner.

Ska arrived as Caribbeans were on the move, thanks to relaxed immigration laws in the U.S. and Britain. Bennett joined the exodus after a two-year stint with Byron Lee & The Dragonaires. And while the Brixton section of south London or Harlem were natural options, Bennett left for Toronto in 1965. “I just wanted to take a break and relax,” he says. Instead, he shook up the Canadian music scene and changed the lives of countless bredren back home.

Between freezing temperatures and a lukewarm reception at pubs and clubs, Jamaicans in Toronto received the cold shoulder. But the West Indian Federation (WIF) Club was launched to give Caribbeans a place of their own. After successfully pairing Bennett with pianist Dizzy Barker, WIF Club owners asked him to start his own band. “I knew the guys in Montego Bay had to be involved,” says Bennett. The group would also include Wayne McGhie.

With folk rocker Joni Mitchell dominating the scene, Canadian music was in a state of introspection. Anyone looking for action had to venture underground to Club Jamaica or Le Coq D’or, where Jo-Jo & The Fugitives thrilled Jamaicans and Canadians with shows that mixed ska, rocksteady and funk. “We kicked some serious ass.

Since many of us were from Montego Bay, we knew different styles of music and how to be versatile for tourists,” says Douglas, who also made the trek to Toronto and became active in the scene. Lloyd Delpratt, 64, a keyboardist for The Fugitives, says those were some of the best years of his life.

“The clubs used to be jumping. People came out to celebrate and enjoy the music.” Equally memorable was the friendship that he struck up with McGhie. “I liked him immediately,” Delpratt says. “He wasn’t trying to imitate Sam Cooke like everyone else.”

Friends remember Wayne McGhie as warm, quiet and easy-going. On stage, however, something took over, forcing him to surrender to the orgasmic-like euphoria that the Fugitives regularly sparked. “One Saturday, we were jammin’ and all of a sudden I saw Wayne playin’ the guitar from the back of his head,” recalls Bennett. “He was playin’, dancing and singing at the same time. The crowd really got wild.”

Times were good for McGhie. By 1968, he was a Canadian citizen and married his Jamaican girlfriend, who gave birth to their only child, Marnie. The next year, he helped his sister Merline migrate to Canada. “He was hardly home,” she says. “He was always on the road.”

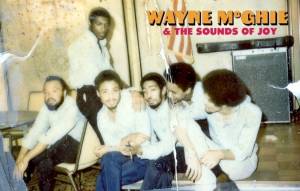

Musician Wayne McGhie (sometime) in the 1970s.

Despite the buzz, the mainstream didn’t know what to do with the Jamaican artists. And given the racial climate, largely didn’t care much anyway.

Bennett, for example, says The Fugitives were thisclose to landing a deal when a record exec suggested they add a white musician. “Racism was different here,” says Everton Pail, 56, a drummer who performed with McGhie. “In America, someone would say ‘Get away from here nigger.’ But someone in Canada would put their arm around you and pretend to be your friend.”

Cemented by a shared history and a genuine love for the music, the men forged a deep kinship. “We hopped from band-to-band and played for whoever needed us. If one of us made it, then it would help all of us,” says Delpratt. If anyone seemed ready to break on through to the other side, it was McGhie.

Following a stint with Delpratt’s band, The Sounds of Joy, McGhie decided to produce a solo album. Surprising many, he tapped producer Art Snider, who was posthumously inducted into the Canadian Country Music Hall of Fame in 2002, to helm the project. “I couldn’t see them getting them along.” remembers Delpratt. “Snider only wanted guys who copied Sam Cooke – and Wayne was original.” But once McGhie began recording, there was no doubt who was in charge.

Since the recording costs were self-funded, McGhie and his musicians were in a race against time. Barring the typical studio hiccups, the performances were flawless. “Wayne used a ghost voice to sing us through the arrangements and played the guitar,” says Delpratt. “He went back to the studio on his own to lay down vocals.” From Everton Paul’s stunning open drum break in “Dirty Funk” to the foot-shuffling reggae cut “Cool It,” the riddims were infectious.

And song after song, McGhie proved to be the consummate soul man, churning out tender and angst-ridden love tales. His slightly raspy voice commands attention on a passionate rendition of “Going In Circles” and soars on “Fire (She Needs Water),” where his piercing screams capture the song’s urgency.

Once the album was completed, Snider sold it to Quality Music. It was the first full-length release by a black man in Canada, but with promotional support from neither Quality nor radio stations, the Wayne McGhie & The Sounds of Joy LP bombed.

Even worse, an accidental fire ripped through Quality’s warehouse and destroyed the remaining copies that weren’t in circulation. Meanwhile, McGhie was in the midst of a personal crisis as his career wreaked havoc at home. “His wife wanted a divorce,” says Merline. “And when Wayne went to see his daughter, she put a restraining order on him.”

It became increasingly difficult for McGhie to grasp the world. Disco arrived by the mid-’70s, forcing his bandmates to look elsewhere for gigs. McGhie never bothered to make a transition.

No one knows what caused the change – associates blame everything from drug abuse to a chemical imbalance – but there’s no doubt that when McGhie appeared at his sister’s apartment in 1979, he was a very different man.

“He came with a Bible and all these books, saying that he could heal people,” recalls Merline. “When it comes to family, I’m there. So I asked him ‘Where do you live?’ And he told me ‘Everywhere.’” McGhie moved in, but domestic comfort only brought temporary relief.

He often disappeared and aimlessly wandered the streets. At home, he frightened his sister. “We lived on the 11th floor and Wayne used to get on the balcony. He said someone was talking to him, but I was only hoping that he didn’t jump,” she says. She contacted social service agencies, but was told that nothing could be done unless he committed a crime. Merline concocted a story that he threatened her. “I felt so bad, but he needed help,” she says. McGhie was admitted to a mental institution.

As word of McGhie’s condition spread, Everton Paul went to see him and found a broken man. “He was distant and didn’t really speak,” says Paul. But the medication he received appeared to work. Soon after his release, McGhie was stable enough to accept an invitation to perform in Chicago.

But when the gig ended, he was shattered. “That brought him to his lowest point. He said that ‘Nobody wanted him’ and he left,” says Merline. Six months later, a New York homeless shelter called Merline to say that McGhie was there. Jay Douglas was stunned when he ran into McGhie at a Toronto donut shop in the early 1980s. “He didn’t look well,” recalls Douglas. “I gave him my number, but I didn’t hear from him.” Neither would the rest of the world.

Since 2001, the Seattle-based record label, Light in The Attic, has been stirring up the underground, producing shows for Saul Williams and reissuing classics from artists including The Last Poets. Its co-founder Matt Sullivan, 30, knows how competitive the market for rare ’70s grooves is.

But this story sounded, well, odd. His friends – Mr. Supreme and DJ Sureshot (collectively known as The Sharpshooters) were pressing him to reissue an album they recently acquired. It was going for $600 on eBay. Yet when The Sharpshooters played a copy of Wayne McGhie & The Sounds of Joy LP for Sullivan, he was blown away. “I must have played it a thousand times.”

A feeding frenzy for McGhie’s album ensued as John Carraro, a New York record dealer bought it in Toronto in the mid’-90s. Pete Rock and Q-Tip became hip to it. And the race was on to find McGhie. In 2003, Sullivan entered the fray. The Sharpshooters suggested he contact Kevin Howes, a writer in Vancouver who DJs under the pseudonym Sipreano. But Howes was at a loss: “You would Google ‘Wayne McGhie’ and there was nothing.” Sullivan and Howes dug for leads and built a database of contacts.

In their search, they also uncovered long-buried history. “When we started to find people who knew Wayne, it was asking all these Jamaicans who came to Toronto in the ’60s to play music. As a white guy who grew up listening to Nirvana in the ’90s, that sounded like the weirdest thing in the world,” concedes Sullivan.

Last summer, Howes attended a wedding where Jay Douglas and his All-Star Band performed. After his friend struck up a conversation with the veteran singer, Howes scored Douglas’ phone number. Sullivan placed a call. “He said it was about Wayne McGhie. I said ‘Wayne McGhie? What did he do?” remembers Douglas with a laugh. “Matt told me what he was doing, but I didn’t give it much thought because there’s so much jive in this business. Then he called three more times and I knew this was serious.”

The one constant in McGhie’s life was his sister Merline. Douglas knew that finding her was critical. “I had to go through so many cats,” he says.

But he finally made contact when he tracked down a friend of Merline’s husband. Douglas last saw McGhie at the shop and had no idea what state he was in. “He was in this little room with a guitar that he hadn’t played in years,” remembers Douglas. “I apologized to him for everything and we reminisced. But he still wasn’t the same.”

Still, Douglas recalls that McGhie was excited when mentioned that a record exec and a DJ wanted to meet him. After months of searching, this encounter seemed daunting.

“We didn’t want Wayne’s family to think that we were trying to exploit him. This is something we felt passionate about,” says Sullivan. That night, they ventured through a punishing snowstorm to meet McGhie – and they were immediately put at ease.

Through Douglas’ playful prodding, colorful stories about McGhie filled the room. And without any prompting, McGhie gently strummed a new guitar that Sullivan brought as a gift. “What dem youts did for Wayne blows my mind. It just shows that music has no color,” reflects Jo-Jo Bennett. With McGhie’s blessing, Sullivan turned his attention to the album itself.

Some decisions came together easily, like assigning Howe to write the album’s liner notes. “A lot of this amazing history could have been lost forever, so we need to appreciate it,” he says. Other decisions – like deciding who receives some of the future royalties – remain complex. “I wish Wayne owned all the publishing, but remembers selling it to the label. Quality went bankrupt in 1982, so we still don’t know who owns it,” says Sullivan.

Released in May, the album has garnered worldwide attention – and Sullivan’s phone has been ringing non-stop. But nothing prepared him for the call he received from Merline’s daughter, Marnie. A musician herself, Marnie, 36, was taken aback when she read about the album in a newspaper recently. “He was always close to my heart,” Marnie says. She reunited with her aunt and called McGhie.

“A lot of things have been coming at him. His album is being revisited, he’s finally getting the attention that he deserves and now his daughter is here,” says Merline. “We have a lot of ground to cover, but we’re playing it by ear.”

These days, McGhie – who isn’t granting interviews – quietly basks in the glow of newfound celebrity. He’s weathered enough storms to appreciate the irony of hearing ads for his album on radio stations that once shunned him.

And while the question of unrealized potential may forever linger, he’s come to accept that life goes on. “Wayne has improved so much. He takes his medication. He’s really been good,” says Merline. “I keep telling Wayne that when I get a little money, we’ll visit Jamaica again – I just won’t let him out of my sight.” She may not have to worry. By facing the music, McGhie may have finally conquered his demons.

“Finding Wayne McGhie” appeared in Issue #45 of YRB Magazine in the spring of 2004.

Add Comment