By Curtis Stephen

My elder brother, Mervyn, had a knack for posing heavy questions. He once asked me whether I ever thought about a day — perhaps a century from now — in which just a handful of people could actually say that we existed.

No, I hadn’t.

No, I hadn’t.

But it was an indelible question that I’ve never forgotten. And the same can be said of him. This week marks ten years since Mervyn’s passing on Nov. 30 –– of a pulmonary embolism –– when he was just 49 years old.

His sudden death sent shock waves that would ripple well beyond his family. That’s because for some three decades, Mervyn had a far-reaching impact on countless lives in his adopted home of New York City.

In his name, District Council 37 –– the largest municipal public employee union in New York City –– made a generous donation to the Bedford Stuyvesant-based criminal justice reform and youth advocacy group, the Center for NuLeadership on Urban Solutions.

(Mervyn was a proud member of DC 37 and a friend of its former leader –– the longtime formidable activist Lillian Roberts.)

At his memorial service, a second room was needed to accommodate the overflow of mourners. His family members and friends were legion. Also there, Richard Green –– founder and CEO of the Crown Heights Youth Collective — who had known Mervyn for decades.

And the New York State Supreme Court Justice Sylvia O. Hinds-Radix was in attendance too. (The judge had only learned of the service hours earlier, but raced over to pay her respects given the grassroots efforts that he waged –– with full pride in her Caribbean roots –– while promoting her first campaign on the streets of Brooklyn.)

And the New York State Supreme Court Justice Sylvia O. Hinds-Radix was in attendance too. (The judge had only learned of the service hours earlier, but raced over to pay her respects given the grassroots efforts that he waged –– with full pride in her Caribbean roots –– while promoting her first campaign on the streets of Brooklyn.)

The attendees were Black and White. Young and old. Christian and Muslim. Those of means, those without. Steeped in symbolism, it was a fitting tribute –– one that is particularly poignant these days –– to someone who proudly touted the immigrant experience in America.

It didn’t matter where you –– or your parents –– were from. Mervyn genuinely wanted to learn how you factored into the nation’s cultural ethos. And to surely discover a brand-new word or two.

Mervyn, after all, could fully relate. Born in Manzanilla, a town on the eastern coast of Trinidad, Mervyn was a teenager when he migrated to Silver Spring, Maryland. That’s where he reunited with our mother, who had resettled in the district in 1973.

Some three years later, Mervyn had (somehow) managed to convince our mother to move to a very daunting New York City –– which he had instantly fallen in love with after visiting a family friend. Years later, he’d tell me that nothing impressed him about the city more than the chance to meet anyone who, quite literally, could be from anywhere.

“There’s nothing like New York,” he once said. “Everything is here.”

Mervyn in 1979.

When Mervyn attended George W. Wingate High School (Class of 1979), he did so at a time when his West Indian accent could easily have rendered him –– at least in some quarters –– as the very last thing that a teenager desired to be: a curiosity.

This was, after all, a time before Wyclef. Before Nicki Minaj. Before Rihanna. Even Bob Marley was still trying to broaden his appeal in the States back then.

Nevertheless, Mervyn knew that all he could ever be — and in time, this would include the plaits and dreads that he proudly wore — was himself. (Years later, he’d play the Sting song “Englishman in New York” endlessly with its refrain: “Be yourself, no matter what they say.”)

As a first-born son with six brothers, Mervyn was keenly aware of his status as a role model. He worked an after-school job at the Brooklyn Public Library and freely gave up his paychecks to our single-parent household.

After graduating from the New York City Institute of Technology, he worked for the Department of Environmental Protection Agency (DEP) for more than 25 years — where he was still employed as an engineer at the time of his passing.

It would have been easy for Mervyn to largely focus on his own needs. Adjusting to life in the Big City, and navigating life as a Black man in America –– as he’d be the first to say –– was anything but easy. And while he’d spend each day on self-improvement, he also had a tendency to look beyond himself.

On Election Day, for instance, he’d cast his vote and then spend the rest of the afternoon and evening driving elderly residents –– completely on his own –– to-and-from local polling stations.

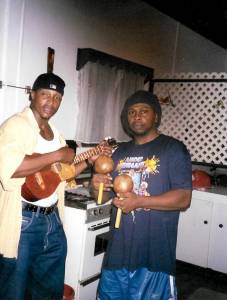

Playing the cuatro with longtime friend Tony Remey in Trinidad.

Whatever the subject, if Mervyn discovered something new — you were bound to learn it too. (“Take a look at this,” he’d say with a gleam in his eye.) He could also be found, from time-to-time, carting around the résumé of someone in full anticipation of the inevitable moment in which he’d meet the right person to hand it over to.

Without fail, each year he would return to Trinidad to recharge his batteries, reconnect with family members, and replenish his soul by taking a dip into the waters along Manzanilla Beach. Still, he could never forsake the hustle-and-bustle of New York.

A soccer ball and music –– with Marley, Dennis Brown and Maxi Priest serving as favorites –– would follow him just about everywhere he went. The laughter and high jinks were ever-present too. (A 20-minute lift, for instance, could easily turn into a 3-hour tour.)

But more than anything — books, especially those about the history of the African Diaspora and her people, served as tools of inspiration and liberation for him.

As I wrote in a 2010 City Limits essay, my decision to pursue a journalism career — at the ripe age of 12 — had surely been influenced by a lot of what he had exposed me to.

He listened to the radio, read the newspapers, watched public affairs shows on television, and placed books like The Autobiography of Malcolm X directly into my hands.

With Mervyn after the release of the City Limits story on Colin Warner.

It was the experiences of those who had migrated to this country that moved him deeply. And it was in that spirit that he took me, one evening back in 2000, to meet a friend of his.

Over the course of some two hours, he told me about the plight of Colin Warner –– a Trinidadian who after some two decades was still incarcerated in a New York prison for a murder he did not commit. Mervyn had casually suggested that I take a closer look at the case, boldly predicting that it would somehow work itself out.

Mervyn with Mom and his siblings.

At that point, I had never written a feature story. But eight months later, when the City Limits cover story appeared on newsstands, it was Mervyn’s vision that came to fruition.

He was also a father and a grandfather. And in the decade since Mervyn’s passing, another granddaughter — as well as several more nieces and nephews — have joined the family.

Of course, they will all come to learn a great deal about him in the years ahead. His legacy is an enduring one — namely, that it doesn’t take much (like those ever transient trappings of fame, money, or a massive pool of social media followers) to make a difference in the life of someone else.

Mervyn did so each and every day. For all those who knew and loved him, our gratitude is eternal.

16 Comments

What a wonderful tribute to your big bro,,Curtis. One of the luckiest events in my life was to be your professor, but actually you are and always have been my teacher!

Thank you for the wonderful sentiments, Dr. Bird. And for taking the time to attend Mervyn’s service. Greatly appreciated then & now.

What a fine tribute! You capture him perfectly.

Very kind. Thanks so much, John.

Beautiful tribute, beautifully written, Curtis. So heartfelt and tender. He lives through you and many others.

Thank you for your sentiments, Marty. Truly appreciated in every respect.

Powerful tribute to your brother. Thank you for sharing this and your storytelling gifts with us.

Thanks for taking the time to read, Rosemary. Appreciate that and you.

Stephen, It was a pleasure reading the memories of your brother Mervyn and how much he meant to you. The article was well written.

Thanks so much, Cindy. Thanks for your positive energy & love always. You well know the power of FAMILY.

This is an amazing Tribute and your brother is smiling up there knowing he lives through you and the family. He was one in a milliom and a blessing indeed!

Thanks very much, Steve. Appreciated Always.

It’s not the time on this earth but the impact. Thanks for this wonderful tribute.

So very true, Lashanta. Thanks for the sentiments and for taking the time to read it.

First time reading this, and it’s all so true ,to this day I miss him Because he wasn’t just a friend to me ,he was my BROTHER, he now lives in my heart until that day comes that we will meet again,he Was a true leader,HOLD IT DOWN ,

Thank you, Tony. And you shall forever be a BROTHER. No doubt that he was grateful for YOU too. So many special memories. Cherish them all.

Add Comment