This story was published in the fall 2011 issue of The Crisis magazine.

In 1989, Troy Davis worked at a construction site and dreamed of joining the Marine Corps. Today he is on death row for being the triggerman in the fatal shooting of off-duty police officer Mark MacPhail in a Savannah, Ga. parking lot that summer.

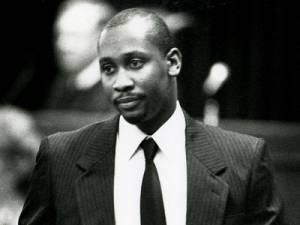

Convicted in 1991 for murdering Officer MacPhail, Davis, 42, is incarcerated at the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison near Jackson, Ga. In March, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected Davis’ appeal for a case review, which clears the way for a new date of execution.

Davis’ legal team plans to petition the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles. “The Supreme Court ruling was certainly upsetting,” says lead attorney Jason Ewart. “We thought there were a lot of issues that they should have considered.”

This wasn’t the first time the case appeared before the U.S. Supreme Court or the Georgia pardons board. And while much of what occurred during the early morning hours of August 19, 1989 is being disputed, one fact remains: Davis and two other men, Sylvester “Red” Coles and Darnell Collins, were in the parking lot of a Burger King restaurant.

Larry Young – who had been drinking with a female companion – was also there. At Davis’ trial, Young explained that after buying drinks at a nearby convenience store, a man angrily accosted him. Coles admitted that Young was referring to him.

Several witnesses testified to seeing one man, and then two other Black males, trail Young. Coles and Collins testified that Davis struck Young in the head with a .38-caliber pistol. Davis, however, testified that Coles was the assailant. On cross-examination, Coles admitted that he carried a gun, but didn’t possess it during his altercation with Young.

Officer Mark MacPhail was shot and killed in Savannah, Ga. in 1989. A father of two, he was 27 years old.

Mark MacPhail, 27, was an officer with the Savannah Police Department for some three years. Married with two children, MacPhail worked as a part-time security guard at Burger King. Witnesses saw him race to Young’s aid as he faced the gun-wielding assailant. Within moments, a bullet struck MacPhail.

Witnesses revealed that the officer was also hit at point-blank range. Coles and Collins testified that they were running when they heard gunshots. Davis said he fled before any shots were fired.

Days after MacPhail’s murder, Davis – who reportedly pleaded guilty and was fined in 1988 for carrying a concealed weapon – was identified by several witnesses through a photograph in police possession.

By then, however, Davis’ face was also visible on widely distributed wanted posters. After a massive manhunt, Davis was taken into custody after a protracted negotiation between police and mediators for the Davis family.

The Savannah Police Department lacked physical evidence. Bullets and shell casings were recovered, but investigators couldn’t find the weapon nor any DNA evidence. Ultimately, the case against Davis centered around witnesses, most of whom identified the shooter by the color of his shirt.

Still unclear is how Davis became the main suspect given that he wasn’t alone. Coles, who confronted Young, was reportedly a suspect initially. “Troy was never questioned,” claims Martina Correia, who is Davis’ sister. “They built their whole case around whatever Coles said.”

It’s a point that Davis’ defense team also raises. “There’s no physical evidence tying Troy and no one else was ever investigated,” says Ewart. “The police failed to consider the alternate suspect.” The Chatham County District Attorney’s Office declined to comment on the original investigation.

Troy Davis in court. (AP photo)

Meanwhile, Davis’ appeals are based on witnesses who have since recanted. One woman said she identified Davis after being pressured by police. And three witnesses reportedly signed affidavits stating that Coles confessed to MacPhail’s murder.

The new accounts have drawn the ire of law enforcement. In a 2008 statement, Spencer Lawton Jr. – the former Chatham County district attorney – mused that the affidavits could have been “paid for, or coerced, or the product of failing memory.” Davis’ lawyers, however, contend otherwise. “Everything that we learned was the result of post-conviction investigations,” says Ewart.

Edward DuBose, president of the NAACP’s Georgia State Conference, believes that Davis’ case warrants another look based on past history. “The Chatham County DA’s Office needs to be investigated by the Justice Department for the years when Lawton was there,” says DuBose, who cited the wrongful convictions of two Savannah men in a 1986 rape that was unearthed earlier this decade. “It’s ironic that the same people they used to convict Troy Davis aren’t credible now.”

In 2009, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered a federal district court in Georgia to determine whether evidence could prove Davis innocent. But the case suffered a setback when Davis failed to secure testimony from Coles.

Federal anti-terrorism legislation, which has increasingly restricted federal courts from overturning death penalty convictions, also proved consequential. Nevertheless, presiding Judge William T. Moore Jr. wrote that Davis’ case “casts some additional, minimal doubt on his conviction” but derided the effort as “largely smoke and mirrors” in his ruling.

“There isn’t going to be a Perry Mason moment where someone gets on the stand and says ‘Don’t take Troy, take me.’ Ultimately, the burden of proof falls on us,” explains Ewart. “But it’s tough to prove anything beyond a reasonable doubt when there’s no DNA, video or other pieces of evidence.”

For many years, Davis’ case was solely the concern of his family. But in recent years, Correia – with support from Amnesty International, the London-based human rights group – has also addressed audiences in Europe about it.

“We have strong faith – and since Troy doesn’t have a voice, I decided to become his voice,” says Correia. “I asked him point-blank, ‘Did you have anything to do with this?’ And he said ‘Absolutely not.’”

In 2009, NAACP President Benjamin Todd Jealous along with Georgia congressmen John Lewis and Hank Johnson visited Davis. Other prominent individuals have called for a review, including former President Jimmy Carter and William Sessions, former FBI director under President Ronald Reagan.

But some observers worry that some of highly publicized efforts could backfire. In June, the Rev. Jesse Jackson vowed to intervene at a press conference, which reportedly rankled some who are directly involved in the case.

Spokespersons for Lewis and Johnson declined to comment, while adding that both are closely monitoring developments. “The publicity cuts two ways. Some of it helps and some of it divides people,” concedes Ewart. “This isn’t a black-and-white issue nor is it a death penalty issue. It’s about witnesses who are saying that something is wrong.”

Meanwhile, after a brief moratorium earlier this year, the death penalty in Georgia has resumed. It’s widely believed that an execution date for Davis will be announced soon – perhaps as early as this summer.

UPDATE: Troy Davis was executed via lethal injection at the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison on Sept. 21, 2011. More than 1,000 people attended his funeral in Savannah, Ga. on Oct. 1, 2011.

Add Comment