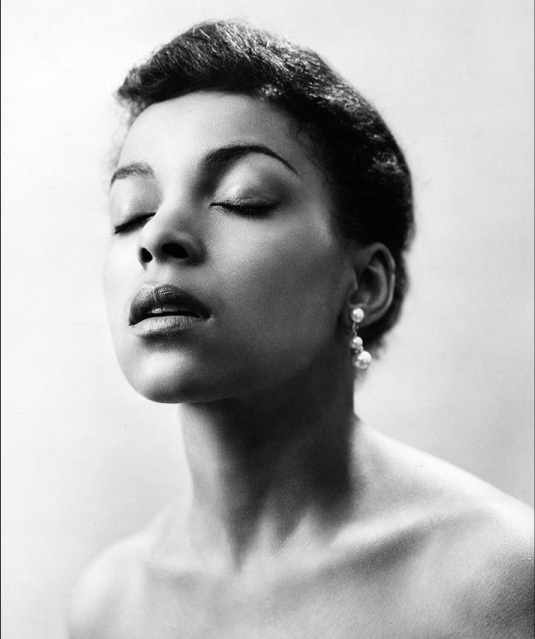

Ruby Dee (Undated). Photo: Everett Collection

With grace, beauty and prodigious talent, Ruby Dee – born in Cleveland and reared in Harlem – had, by December 1969, built the sort of résumé that most actresses in Hollywood, regardless of race, could only dream of.

Whether it was Broadway (starring in a string of notable productions like the rousing 1961 musical “Purlie Victorious”), television (as a series regular on the ABC soap “Peyton Place”) and film (stealing scenes in everything from “A Raisin In The Sun” to “Gone Are The Days!”), Dee was blazing new trails – both in front of and behind the camera.

But as Christmas approached, she was also fed up. It wasn’t the entertainment industry that drew her indignation, though Dee had plenty to say about its systemic lack of inclusion. Instead, it was everything that was happening outside of that world.

Weeks earlier, Chicago police had stormed into an apartment and fired some 90 bullets in a predawn raid – fatally striking 21-year old Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, 22. Both men were central figures in the Black Panther Party’s Illinois chapter.

And in New York, a group – dubbed “the Panther 21” – awaited trial on charges that they plotted to bomb local department stores.

That was part of the bloody, turbulent state of affairs as Dee and family members of the detained Panthers held a press conference inside Manhattan Criminal Court. Yet Dee, who had long championed civil rights and a slew of social justice-related causes, was still taking a major risk by publicly aligning herself with the group.

Dee, however, didn’t care about any potential backlash. With fresh memories of her friends, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. being gunned down, she feared that many more lives were on the line after the shootings of Hampton and Clark.

In helping to launch a fundraising campaign for the Panther 21, Dee appeared before a gaggle of reporters and a bank of television cameras to deliver a strident defense of the detained activists. “They have been held for nine months and the legal fees are piling up. We need help!” she demanded at the press conference. “Don’t wait until it’s too late.” (In 1971, the 21 Panthers were acquitted of all charges.)

It was just one of many suspense-filled moments that Dee recalled when we sat down for a wide-ranging interview about her remarkable life for The Crisis in 2007. At that point, Dee was very much in the limelight after receiving a Grammy Award and with the release of “American Gangster” – a film that would garner an Oscar nomination for her at the age of 83.

But Dee was still reeling from the 2005 death of her husband, the noted actor and playwright Ossie Davis (They were married for 57 years.) In excerpts of the interview that is being released here for the first time, Dee (who passed away in 2014) talks about longevity, her legacy, and performing – as well as speaking out – with Davis.

Ruby Dee (center) at Manhattan Criminal Court in Dec. 1969 press conference on Panther 21 case.

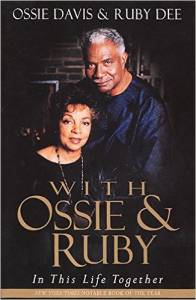

Congratulations on winning your first Grammy [in the “Best Spoken Word” category for the book “With Ossie and Ruby: In This Life Together.”] You’ve already had an iconic career up to this point. But how are you processing this?

That’s right, grandma with the Grammy [laughs]. I was so thrilled. I feel like a rock star or something. I always thought it was something just for musicians. Although, I was so pleased to know that they do an award for voice work, for spoken-word based on the written word. And that pleases me to no end. I think it’s an unrecognized field.

In 2006, the Ossie Davis & Ruby Dee memoir “In This Life Together” was released. The audio version scored Dee a Grammy Award in 2007.

What music is to the musician, the spoken-word is to everyone else. It defines us. It’s an electric impulse as far as I’m concerned. This whole business of speech and different types of speech and where we come from. So many of the painters – they could paint the same subject, but the way they do it is distinctive in very special ways. And that’s what writers do with words.

They spell us out in particular ways, so that different people saying the same words can provide a totally different expression. I’m wondering if the Grammy may have something to do with that kind of appreciation.

So many people love you and are thinking about you. How are you? And what do you miss the most about your husband, whom you shared a lifelong bond with?

I miss talking with him about everything. He loved to do that. We couldn’t stay angry with each other for very long because he would have to talk about something.

He would be reading something and then we would forget about whatever it was that we had a beef about. And we’d begin to talk. He was interested in people and the world.

He was what I call, ‘a lover of people.’ But he was also a lover of circumstances, personalities, and situations. He enjoyed the intrigue and the complications. And he enjoyed trying to figure out how we could get out of them. He would challenge me when I would say something.

For my sake, he would put them into bite-sized pieces. I’d say, ‘Well, you’ll just have to break that down for me.’ That kind of thing. I miss his laughter. He had an enormous sense of humor. So much of what he said was serious, but he would find something ridiculous to point out.

And he would sense that about himself too, even when he went off on the deep end on some kind of thought. He had us all laughing, for example, at his mother’s funeral. But in a way where we appreciated it because he was saying something about our lives – the longing and the loving.

You also have a long established track record of being an activist. There are so many causes that you and your husband took on throughout your careers. Where did that sense of purpose come from?

Dee in 1961 film “A Raisin in The Sun” with (from left) Diana Sands, Sidney Poitier and Claudia McNeil. In 2005, the Library of Congress selected the film for preservation in the National Film Registry. Photo: Everett Collection.

Well, when your back is up against the wall – there really isn’t a choice, is there? My husband was very fond of this expression: ‘If you can’t do anything about it – you have to forget it, down it and get around it.’ He had that ability and it went beyond his own personal take on things. I don’t know where he got that phrase from, but he was always saying that. That philosophical side that he had was always tinged with humor.

Dee and her husband Ossie Davis protest alongside their children (undated).

But really, there was no choice – you couldn’t ignore what was going on. And my husband and I – we were very clear about the sacrifices and the battles that were fought, which set the stage for us. We were not the only ones standing up, of course. In the larger scheme of things, it was never about us.

We had a platform and we used it for those who didn’t have a voice or just couldn’t get the attention. Whenever you’re standing up for justice, you’re standing up for what is right. Just like whatever is going on today. It doesn’t matter how old you are. I’m constantly inspired by the young people. But anyone can stand up at any time.

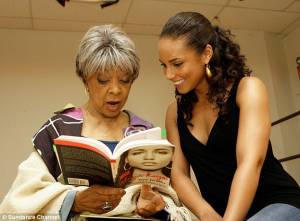

Dee reading recording artist Alicia Keys’ songbook on the SundanceTV broadcast “Iconoclasts” in 2007. Photo: Sundance Channel.

There’s a rumor now that you’re over 80 years old. Where do you get this energy from? And what goals would you like to accomplish now?

The impulse still lives. It’s so strong. It’s so strong that when the body dies, the impulse to live escapes. It’s a phenomenon. As long as the life force has something that can accommodate it. So I don’t have to think about not being energetic or dying or anything like that because I can’t do anything about that. The only job that I have mainly is to live as fully as I can, to rejoice, and to take in what I call ‘the microscopic nature of joy’ – as well as the larger applications – because it’s an extraordinary process.

Courtesy of WPIX-TV, here is footage below of Ruby Dee, citing instances of fatal police shootings, at a 1969 news conference.

1 Comment

Great job Curtis my fellow Tilden alumni . This article gave me life. It’s nice to remember her this black history month.

Erica

Add Comment